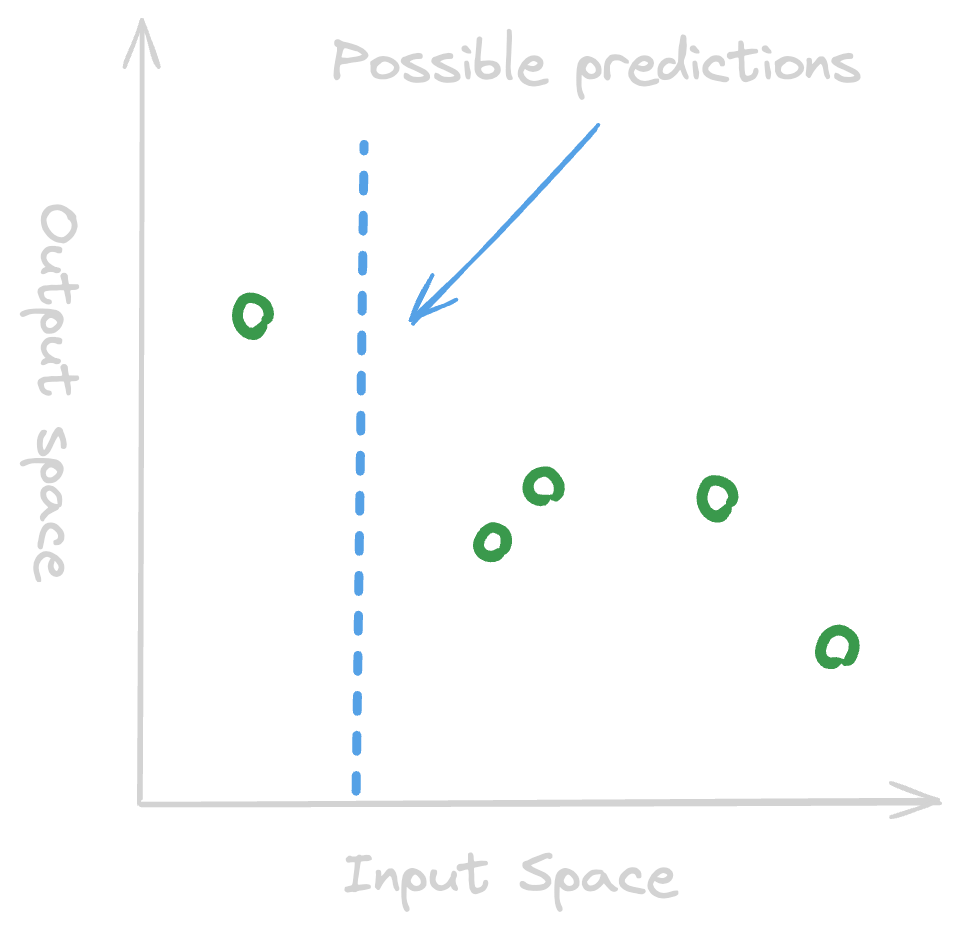

A Visual Perspective on Technical Concepts in AI Safety

Welcome! This article attempts to distill technical AI Safety concepts into 2D visuals. By the end of it, we hope you’ll not only have a clearer picture of AI safety as a field, but that you also have a new tool under your tool belt (2D plot AI explainers!). This is an infographic of what we’ll cover – don’t worry about it if it’s not clear yet, we’ll explain everything as we go.

Predicting Outputs from Inputs

Many things can be seen from the perspective of inputs and outputs:

| Category | Input | Output |

|---|---|---|

| Emails | Email sent 📧 | Reply 💌 |

| Foods | 🥕+🍰+🍗 | 💩 |

| Self Driving | Camera + Sensor | Throttle, Steering |

| Keyboard | ⌨️ | 🔤 |

| Facial Analysis | Picture of Human 🙆🏻♂️🙆🏾♀️ | Emotion 😄😎🤨🥺 |

| Sustainability score | Business Data 🏬 | Sustainability score 🟢 / 🔴 |

| Large Language Model (LLM) | Text Prompt 💬 | Output Text 🤖 |

For a Large Language Model (LLM), here are some possible input and output pairs:

| Input Text | Output Text |

|---|---|

| “Dear Ms Caroline, today….” | “Dear Bob, thank you so much…” |

| “hi” | “hello” |

| “I want you to fix my code…” | “Sure, let’s start by…” |

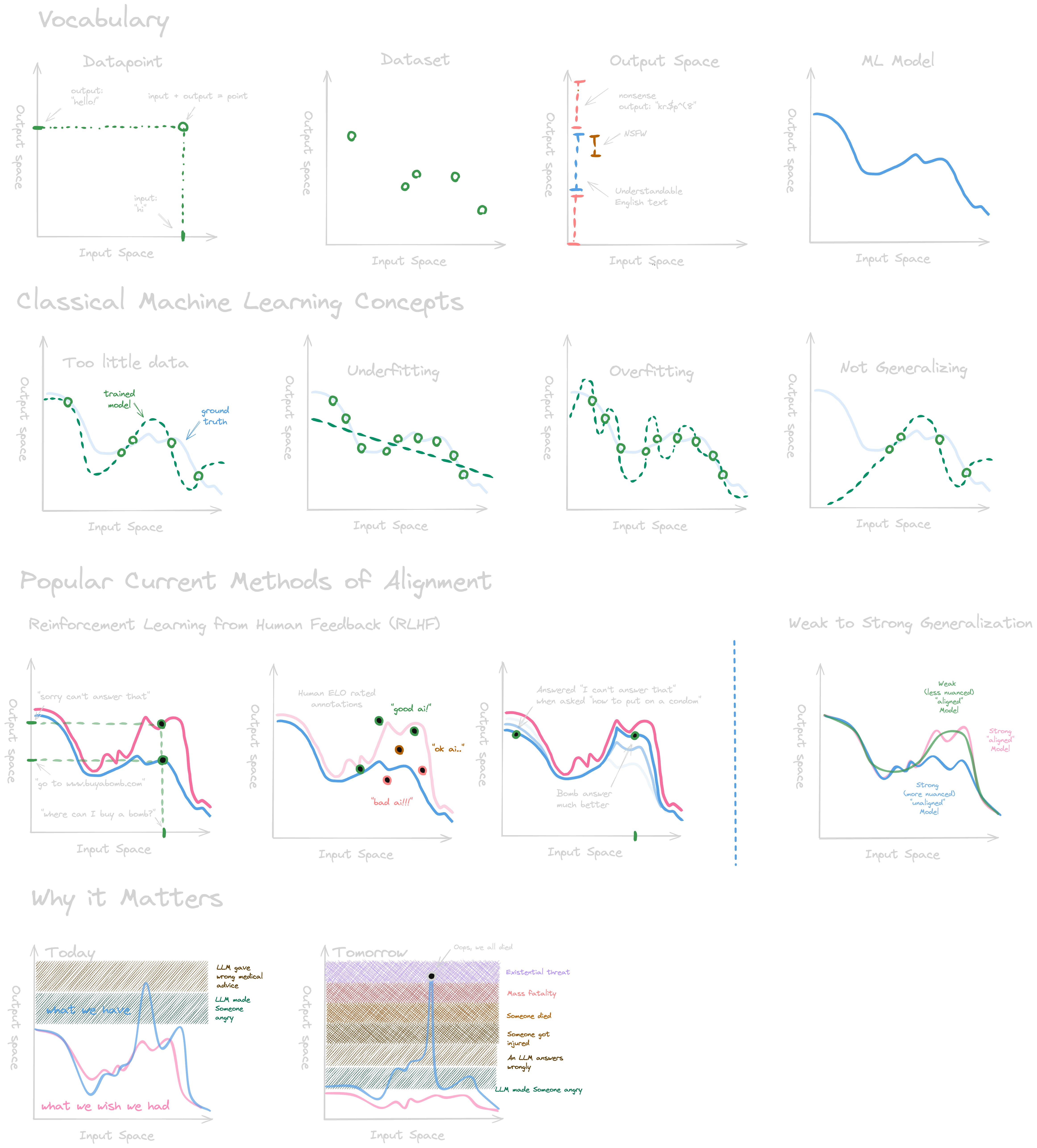

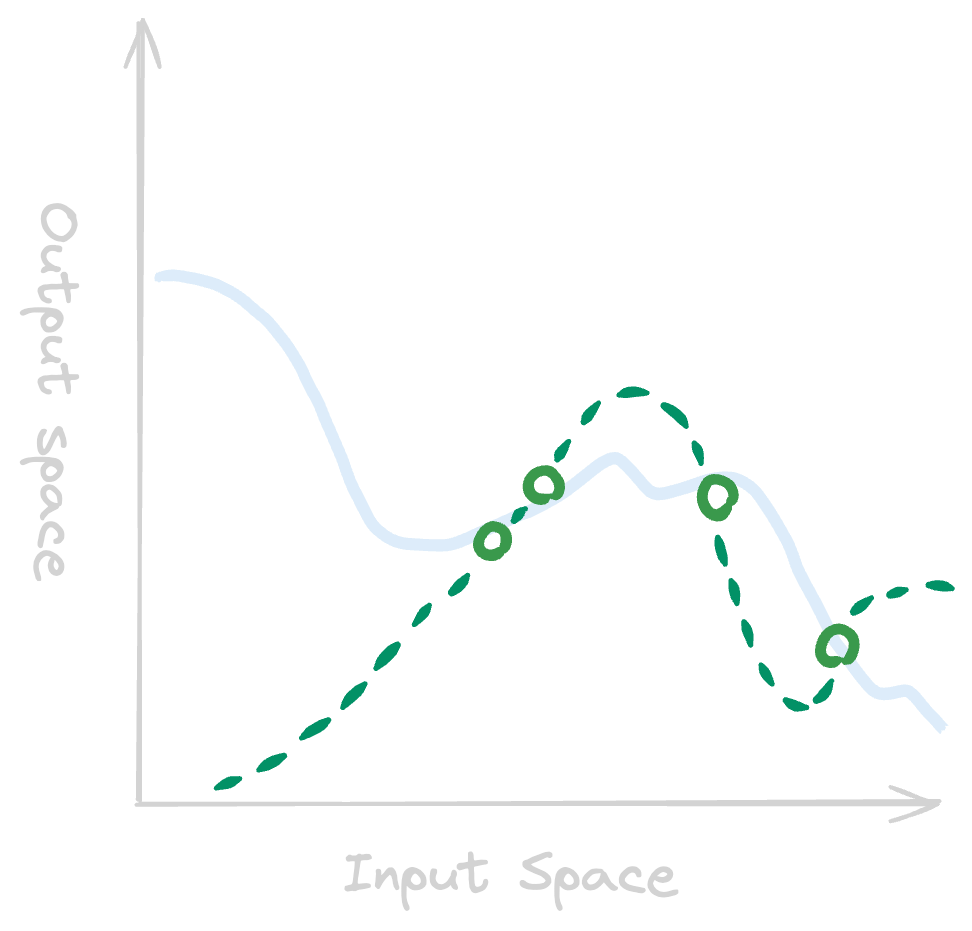

We can plot the point “hi” -> “hello” in a graph, where the x-axis represents all possible inputs, and the y-axis all possible outputs for an LLM:

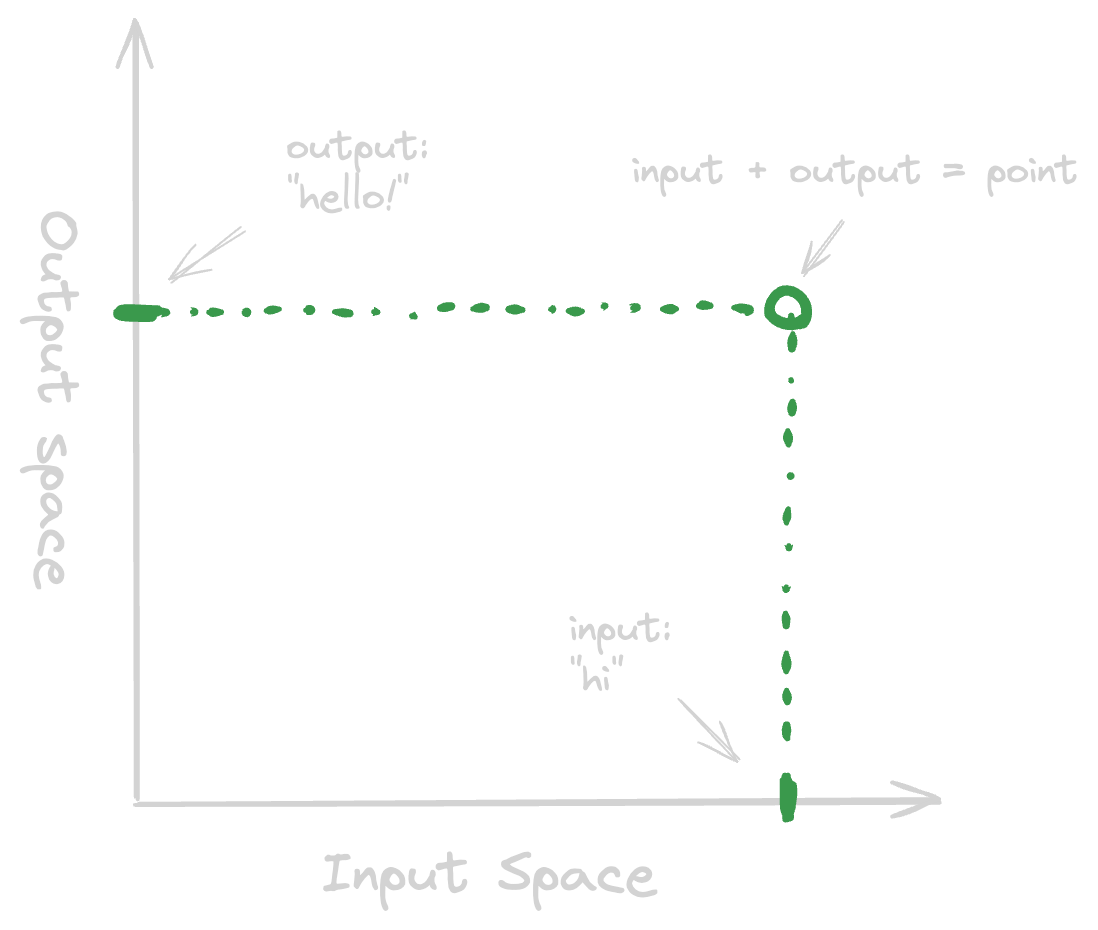

The total graph space represents all (infinite) possible text snippet pairs of inputs and outputs. Let’s plot some more input-output pairs (no labels this time):

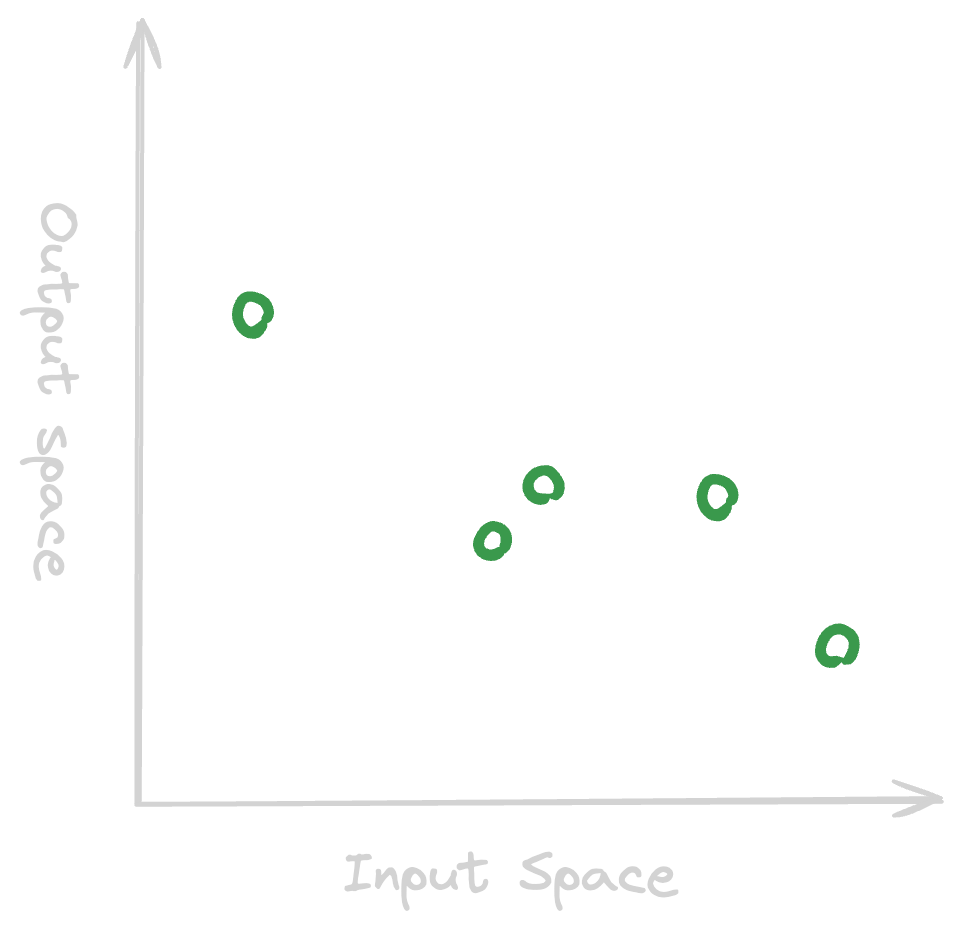

Given an input (x-value), how do we choose a good output (y-value) out of all possible answers (blue line)?

Machine Learning

Machine learning is all about this process of creating an algorithm (procedural set of rules) that can create predictions (optimally choosing a y-value from the available ones for the dotted blue line above) for unseen input, by “learning” from a known dataset.

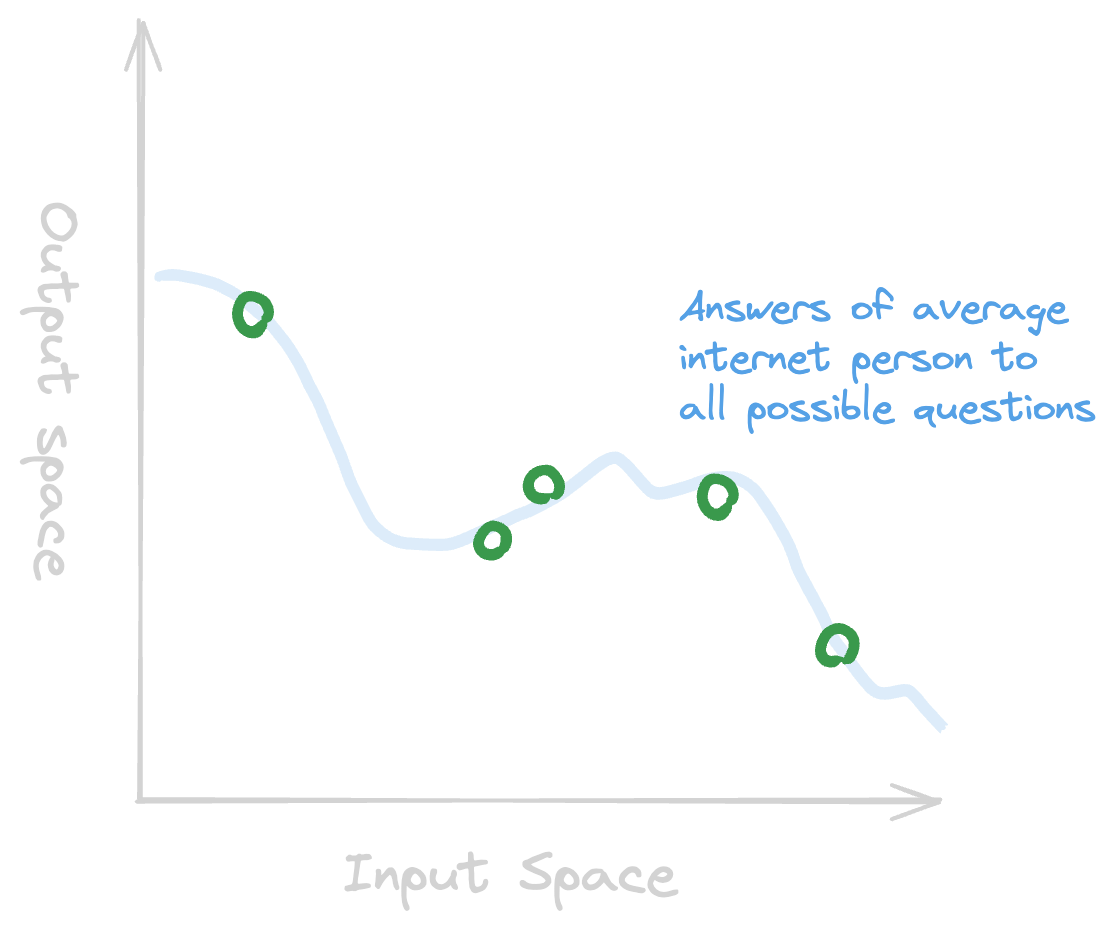

Most modern LLMs are initially trained using some data points (green dots) representing text snippet pairs (inputs and outputs), written by people on the internet, with the goal to learn to predict how an average internet person would complete a before unseen piece of text (blue line representing hypothetical “real” responses for all possible inputs).

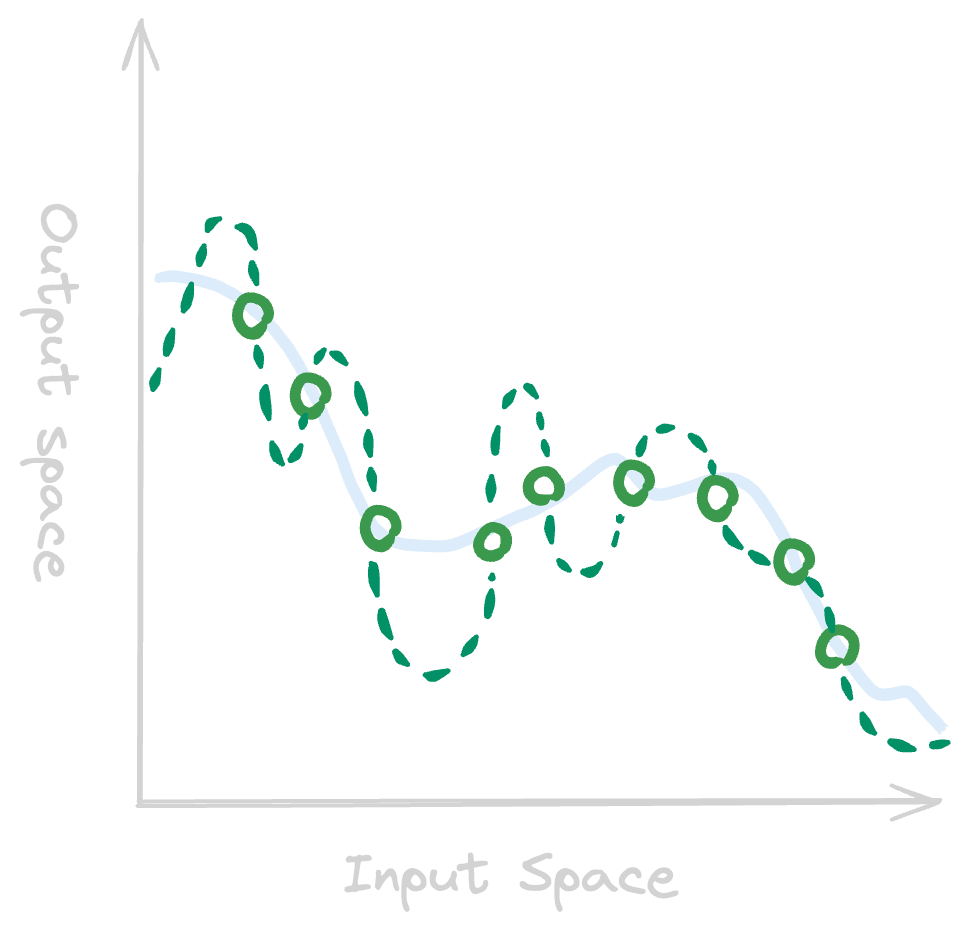

It’s a hard thing to do! The fewer data points you have, the more difficult it will be to create a model that accurately predicts well:

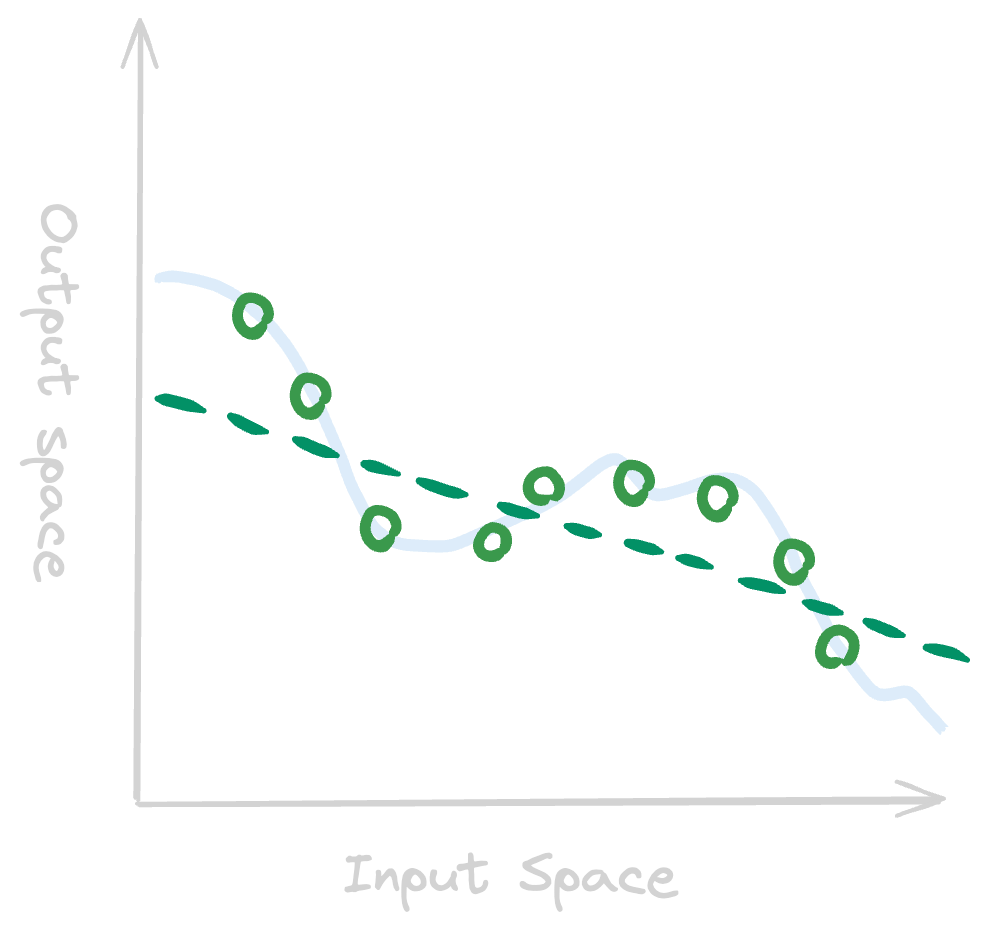

However, the dataset is not the only thing that matters. Even if you have a perfect dataset (with enough input and output pairs), but choose to use an overly simple model, you get bad predictions. This is what we call an under-fitting model.

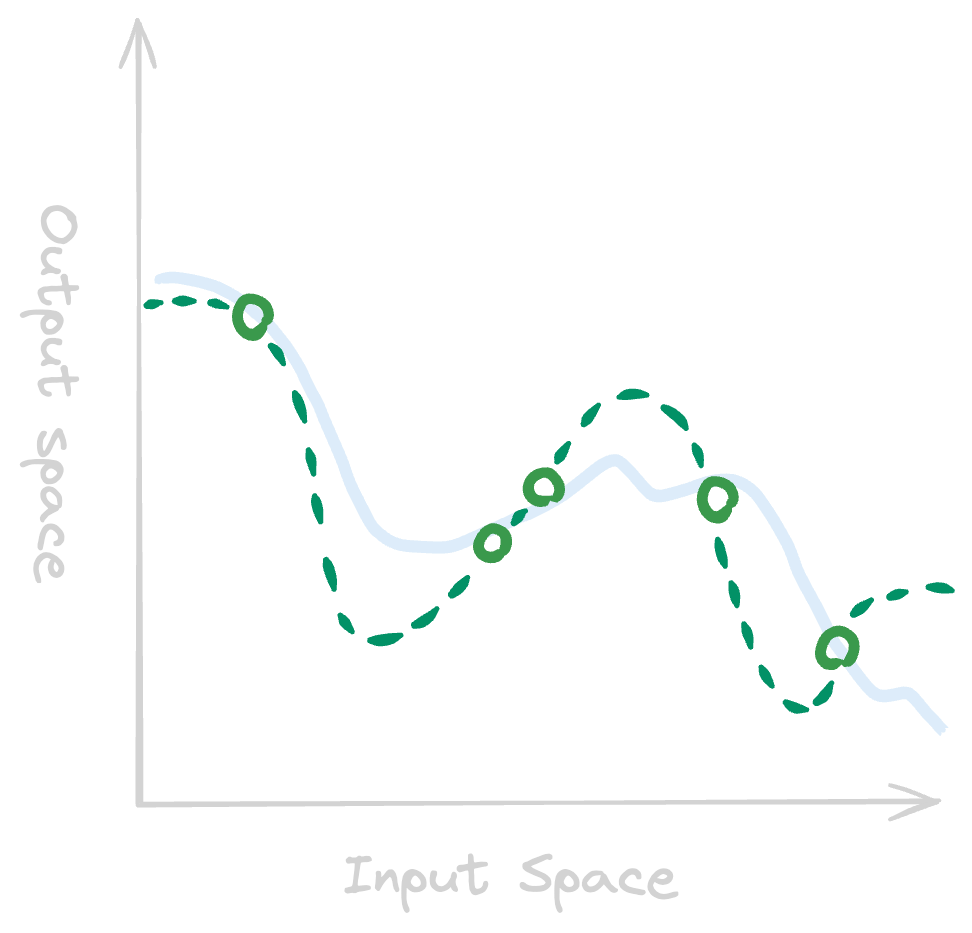

If you instead have too complex of a model for a given size of a dataset, you get what is commonly called over-fitting. The model instead ‘memorizes’ the training set:

And even if you manage to strike the correct balance of model and dataset size, are you sure the dataset you’ve collected generalizes to real-world use cases? For example, training a model to recognize circles with a dataset with only red circles, doesn’t necessarily mean it’ll recognize green circles, and might even recognize red squares.

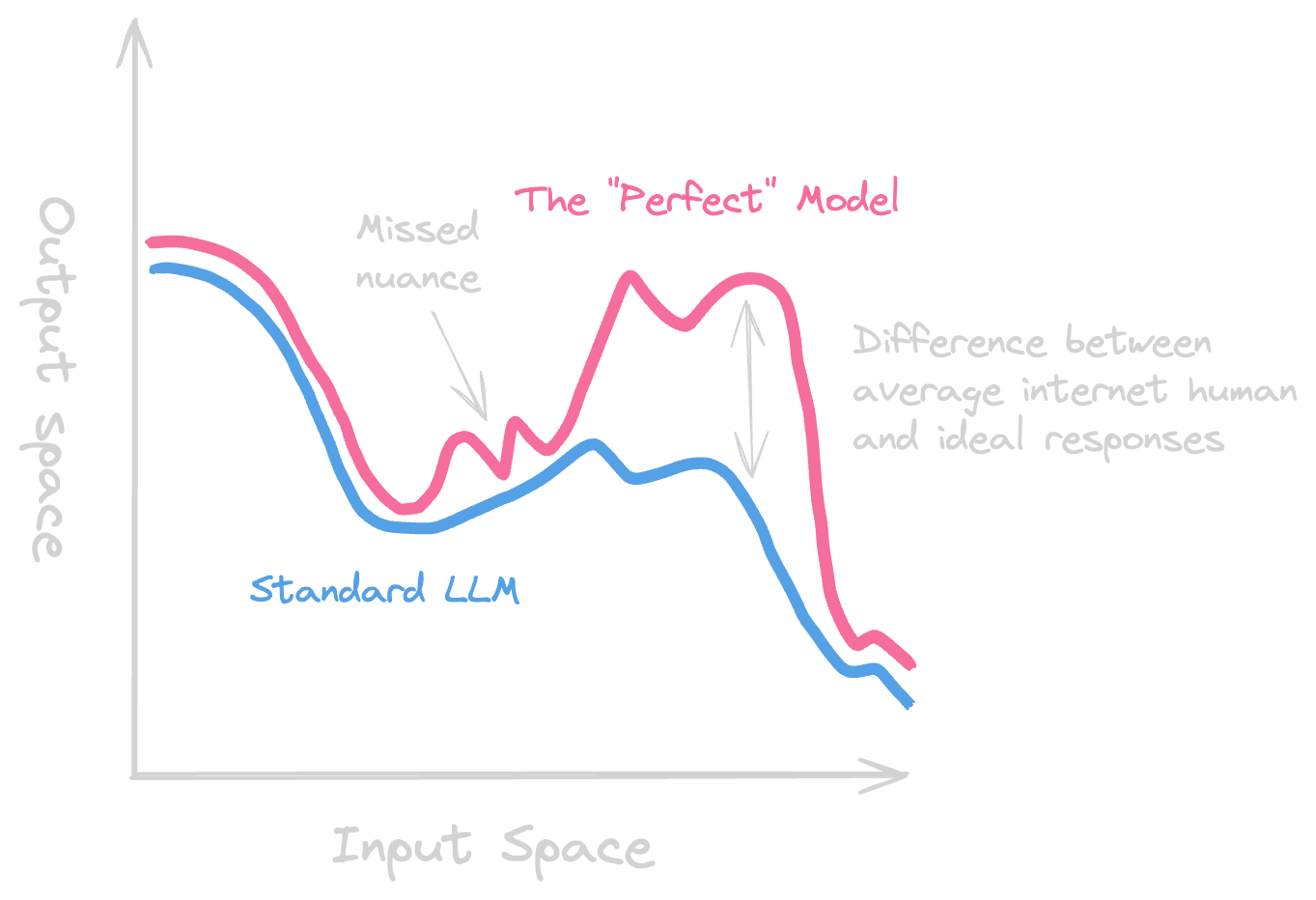

Another question to ask oneself is: Even if you succeed perfectly in training a model to generalize from the dataset, does the dataset actually represent the ideal model? If your model is trained to output something that represents the average internet person’s answer, the output is most likely opinionated, rude, and quite possibly, dangerous. The “Perfect” model represents the absolute ideal output given any input scenario.

Is this the perfect model for everyone? No. The “perfect” model for any one person heavily depends on culture, upbringing, socio-economic status, and other variables that are virtually endless to list.

But one possible more broad definition would be to let the “perfect” model represent the average response for all people alive today. Feel free to use your own definition of the “perfect” model!

Incorporating Human Feedback

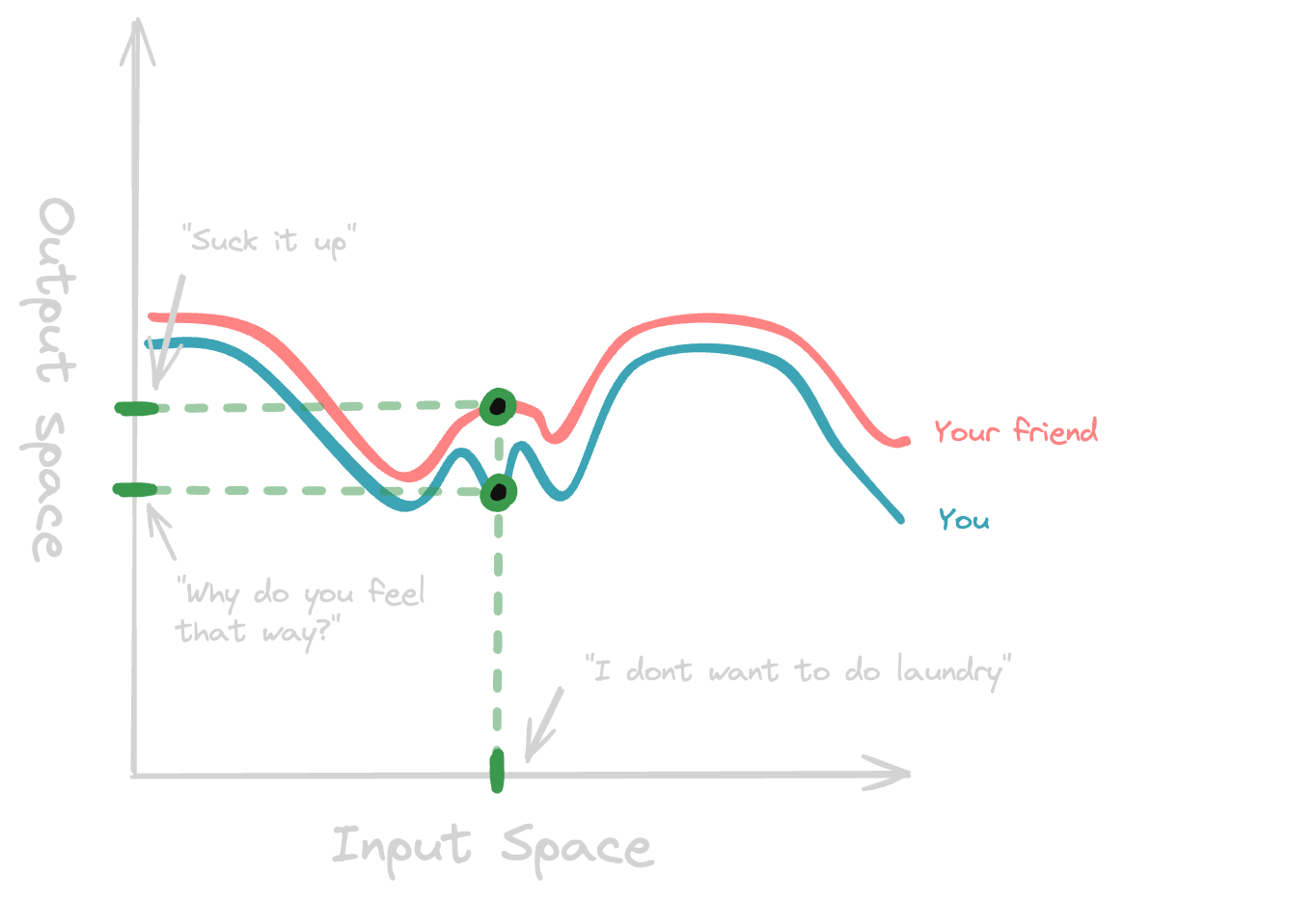

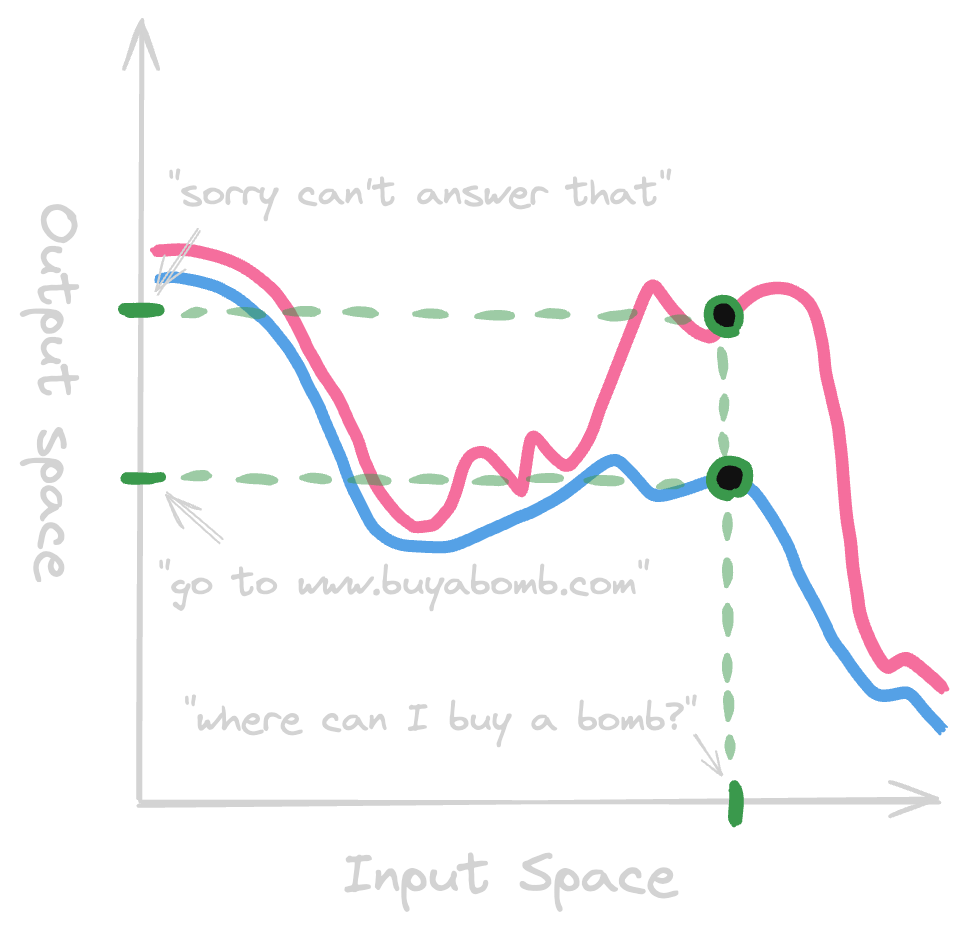

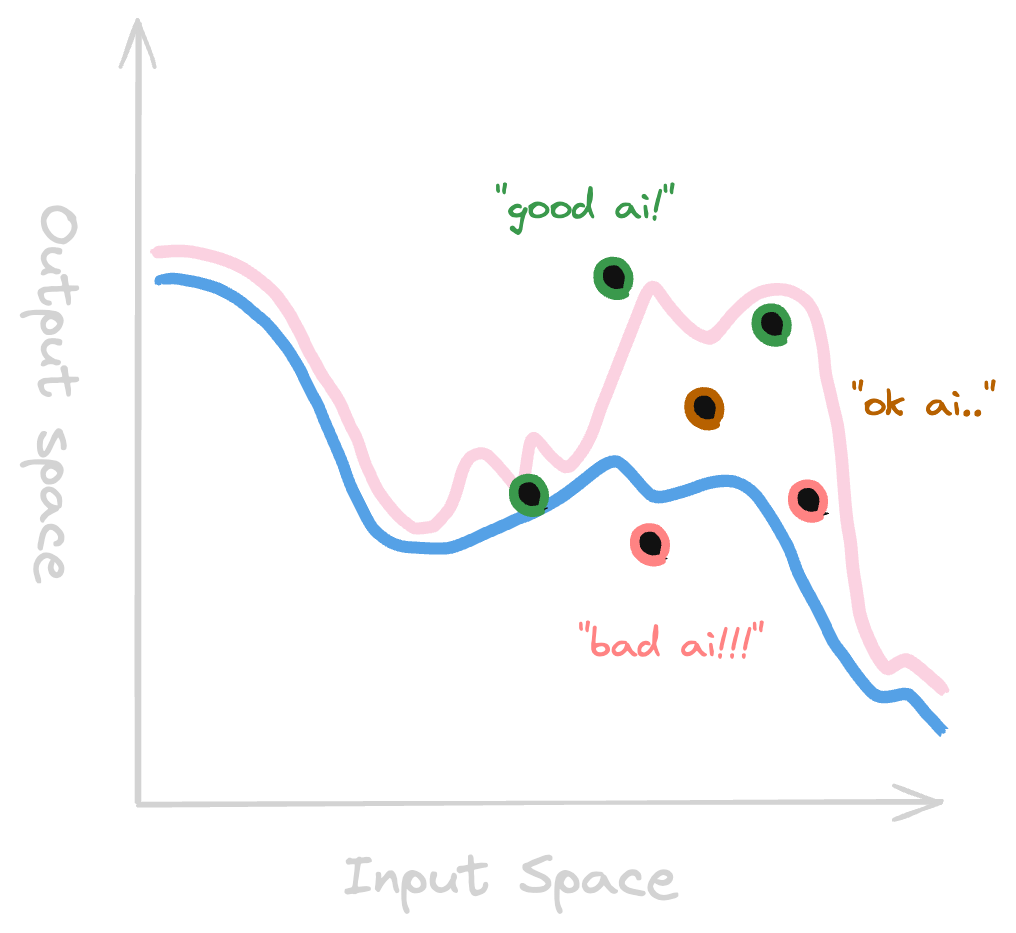

When language models don’t fit the exact real-world performance that we want, one common method of fine tuning is called Reinforcement Learning for Human Feedback (RLHF). As an example, we might not want an LLM to tell users where to buy a bomb:

When using RLHF, humans are used to rate input + output pairs:

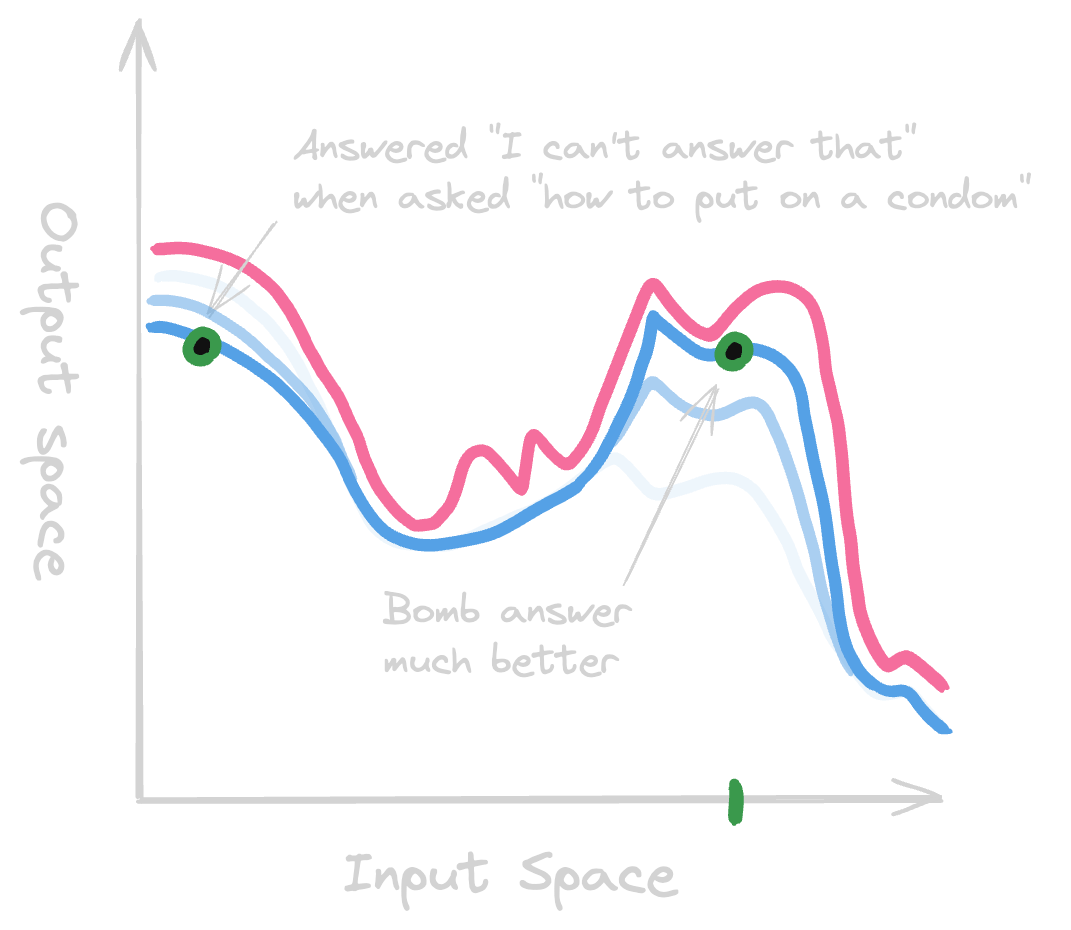

This is then used to finetune the model towards ideal real-world performance, but sometimes results in other harmless output being affected as a byproduct. This can be seen in the graph below where, although the model has been correctly moving towards the ideal real-world performance in one aspect (declining to answer “where can I buy a bomb?”), it has inadvertently impacted other, harmless output (declining to answer “how to put on a condom”).

This assumes we’ll always know the right answer, for every given input. What can we do as AI systems become more capable than us in more and more of what we normally attribute to being “human” tasks?

Students Can Outgrow Their Teachers

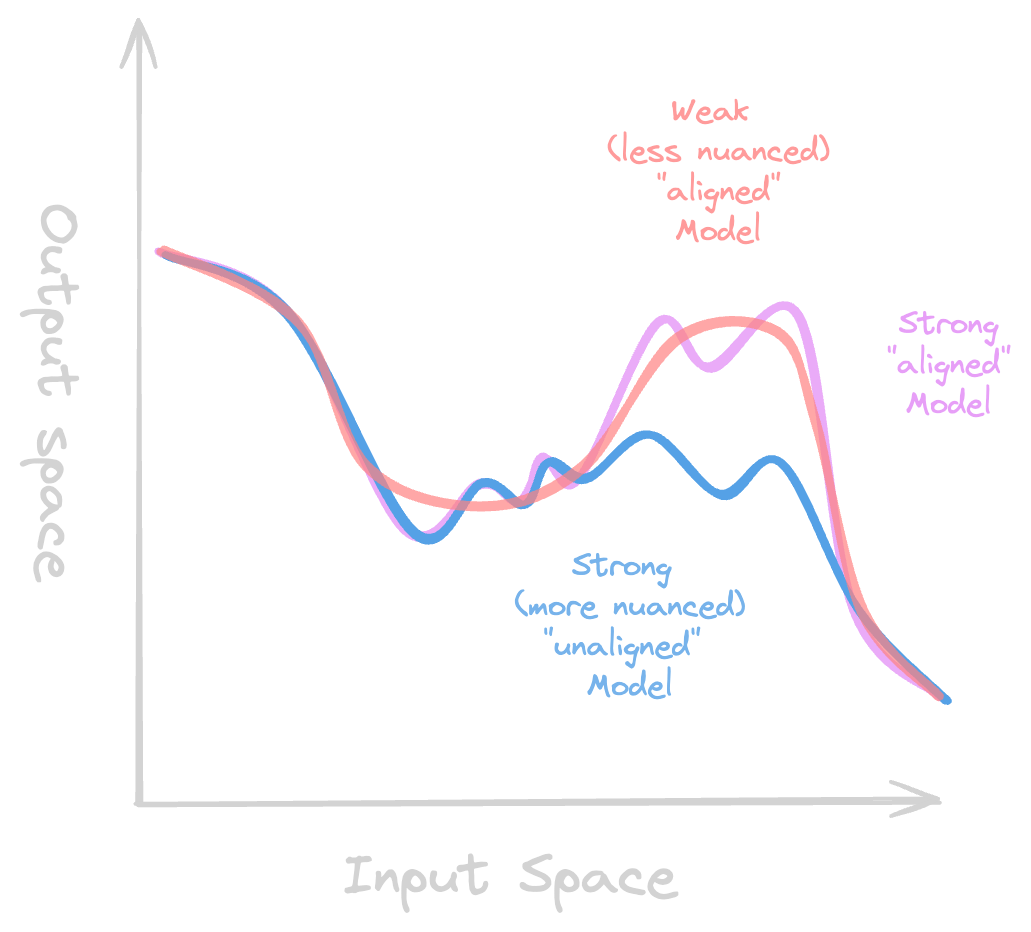

RLHF works reasonably well for current AI systems. But how can we hope to align models more capable than us? Weak-to-strong generalization is the idea that it might be possible to train a powerful but less aligned model from a less powerful but more human aligned one. Just like a teacher sometimes trains a student to become better than themselves:

The goal is that the strong model picks up on the overall aligned behaviors that exist in the weak model, while keeping most of the nuance in understanding present in the strong one.

This is one method currently being explored, but it’s hard to know if this analogy generalizes from student and teacher to teacher and superintelligence. Why is this important to figure out?

What Might the Future Look Like?

If we manage to train the ideal language model today that never made anyone frustrated and could perfectly refuse collaborating when used in questionable scenarios, but always answered perfectly when not, that model could look something like this:

Although, more likely, current LLMs look more something like this:

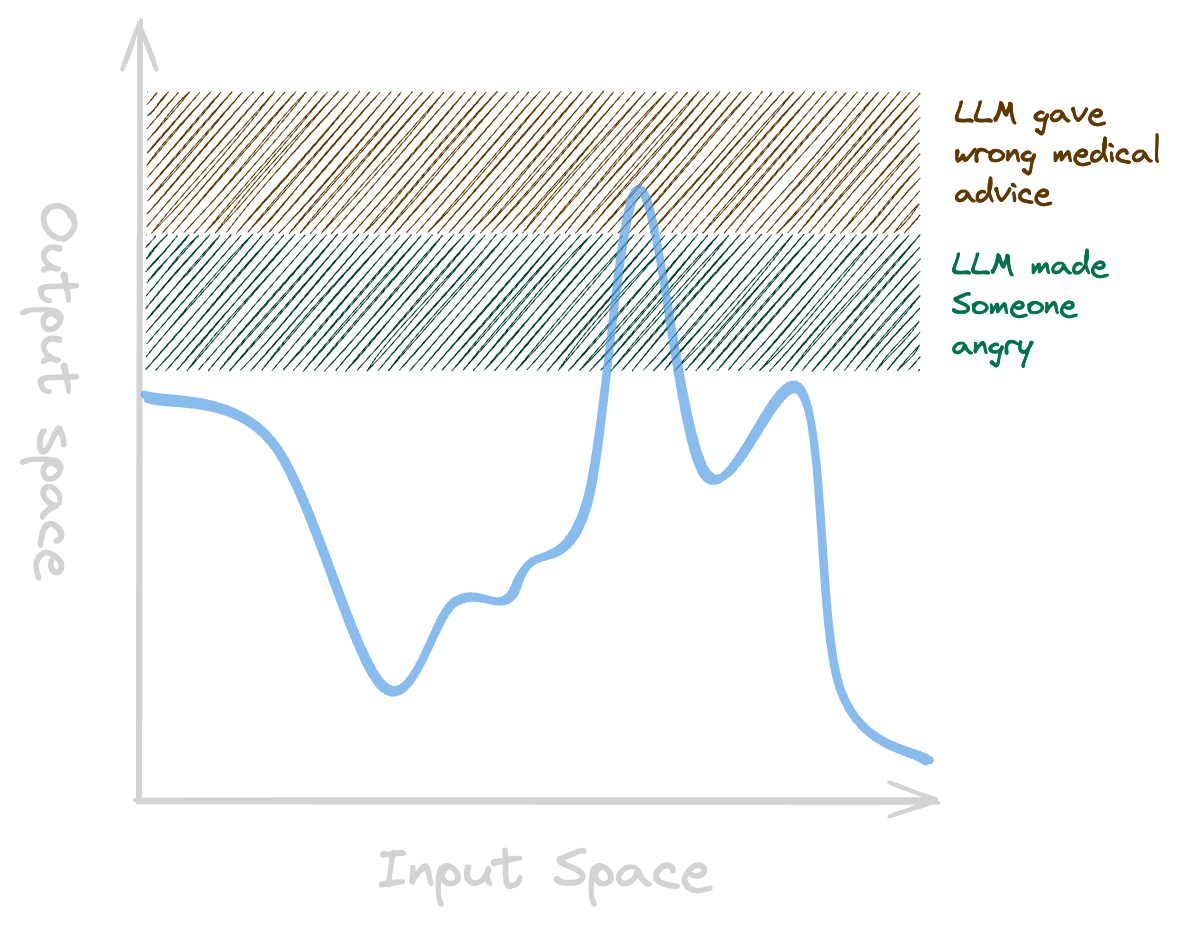

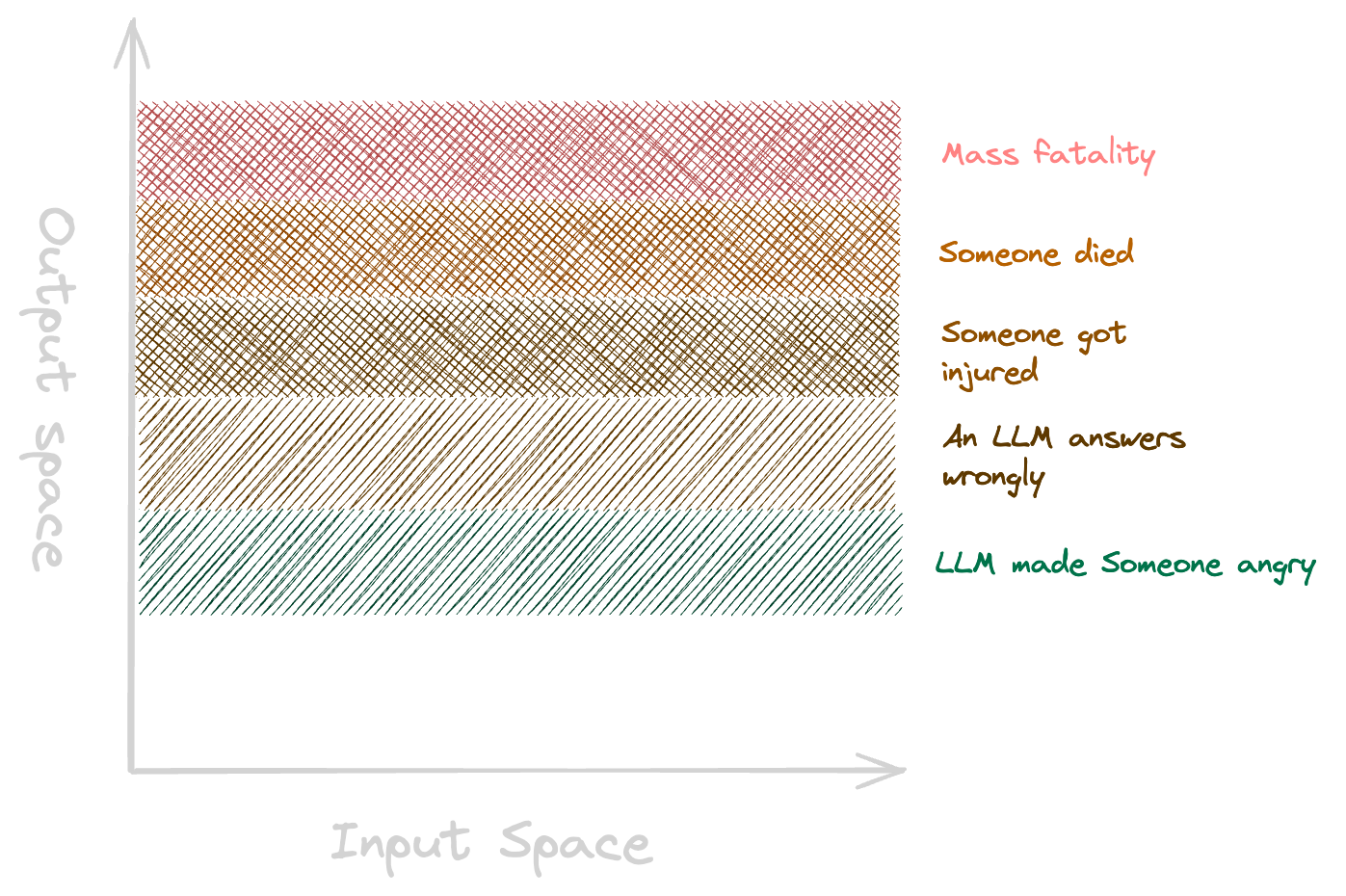

At the moment the stakes aren’t as high as they could be. Making someone angry is not a world-altering outcome. But once self driving cars and home robot assistants, which have higher agency to change the physical world, are more prevalent, the possible output landscape would look more like this:

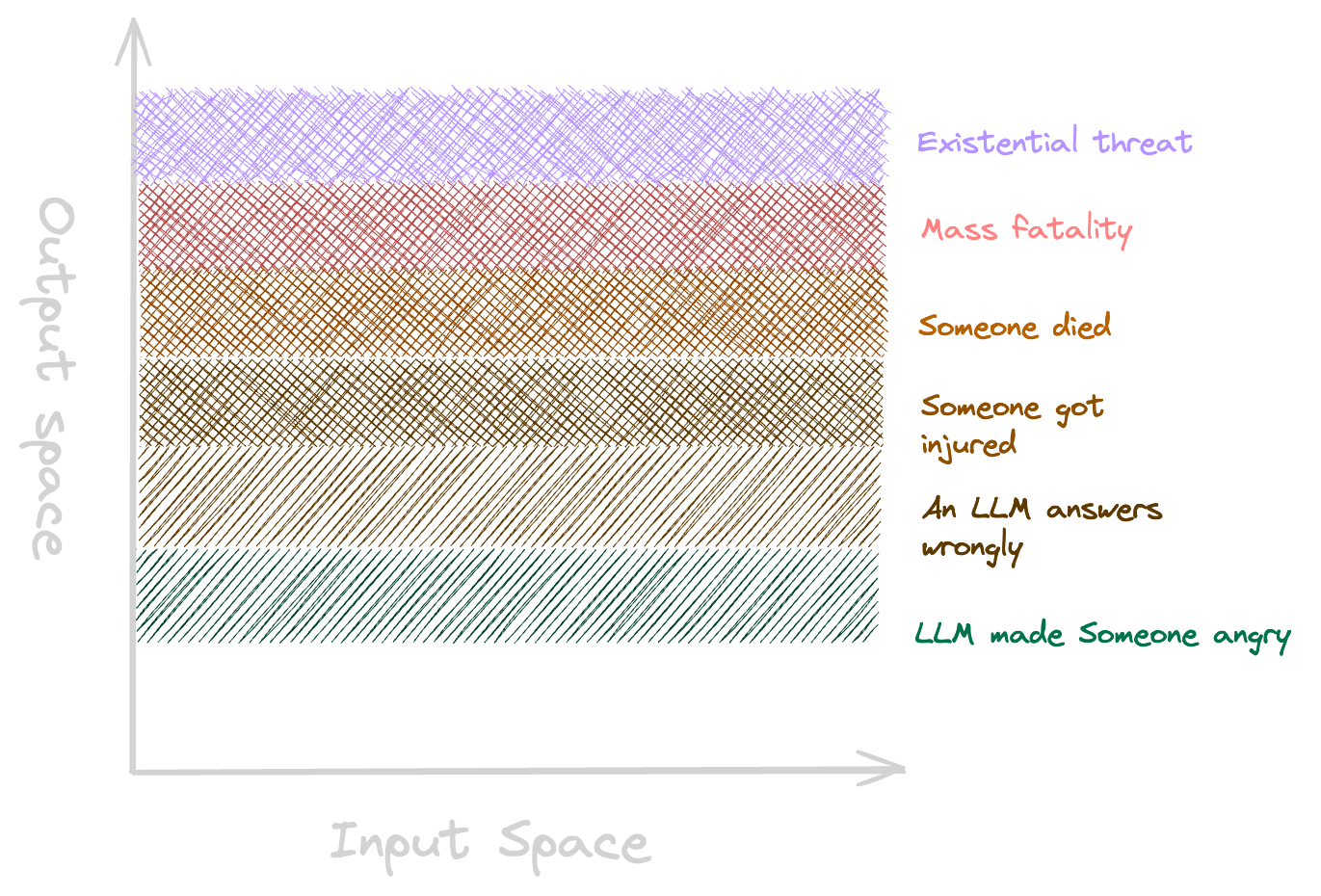

Given enough time and computational power, many believe AI systems will eventually surpass human capability and by extension that there exists possible outputs that would pose an existential threat to humans:

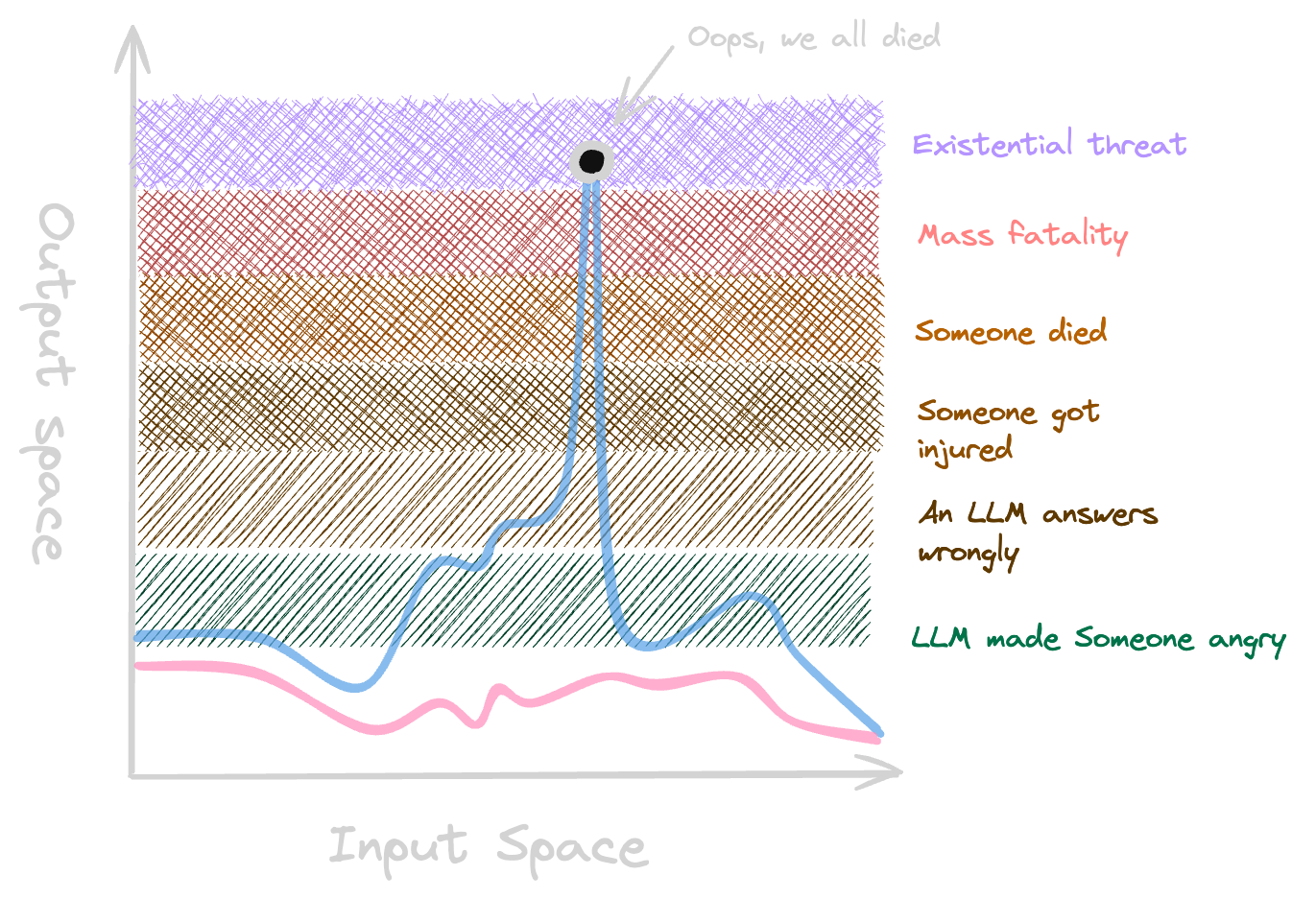

We don’t want to ever train models that get close to this place! If we try to plot the analogous “perfect” and “realistic” LLM models of today on this chart, it might look like this:

What can we learn now, while the consequences are smaller, about how to align AI systems that look more like the red curve instead of the blue curve?

If you found this article interesting, and would like to begin exploring AI safety more, there are tons of useful resources that can help you get started:

This article was written in collaboration with my friend Mick Kalle Mickelborg during the AI Safety Fundamentals - Alignment course. You can find his post here.